Avoid the traps, save time, and build muscle smarter.

Brad is a university lecturer with a master’s degree in Kinesiology and is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) with the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). He has competed as a drug-free bodybuilder, is a cancer survivor, and a 21 year veteran of the Air National Guard. Brad has been a Primer contributor since 2011.

The internet is in no short supply of information regarding the dos and don’ts of exercise selection. It can get downright nasty in some cases. People huddle up in their dogmatic corners always on defense touting their way as the ultimate elixir. From “Never do this” to “Always do that” we are caught in a seemingly endless contradictory ideology of best and worst.

That’s no more apparent than among beginners. As a newcomer, you become a sponge for information. You soak up anything and everything while hoping not to become paralyzed by over-analysis. You’ll hear one thing, and then hear the exact opposite immediately after–sometimes from the same source!

For the record, there are no off-limit exercises. There are, however, optimal exercises specific to very defined goals. For example, if your goal is to pack on muscle and build some strength, then there is a loose list of optimal and less-than-optimal exercises for that goal.

With a focus on packing some muscle tissue onto our frames, the goal will be to overload the chosen muscle group with effective exercises with both efficiency and effectiveness. In other words, we need to find movements that give us the best bang for our buck and not waste our limited time.

Below are six examples of exercises no successful bodybuilder does, but beginners always do, and some things we can do instead. Some of these reasons may sound familiar, but please read on. There might be a few explanations you’ve never heard before.

Behind the neck barbell shoulder press

The behind-the-neck barbell press is notorious for being on the blacklist of worst offenders.

Most trainers will warn of the obvious stress this press will put on the shoulder capsule potentially causing long-term pain and injury. Initially, the upper arm is placed in an externally rotated position (rotating the arm as if backfisting someone behind you in the face) with the addition of a load. With this one-two punch the shoulder area is put in a weak posture and will be less than effective to lift the chosen load. The weight then becomes a danger rather than an advantage.

Two things can be corrected here. One, take the arm out of extreme external rotation, and two, choose a more effective motion to properly overload the deltoids. Fortunately, this is an easy fix.

Grab a pair of dumbbells and raise them to shoulder level. Rotate your upper arms forward by bringing your elbows to the front and your palms facing each other. Think as if you were at the top of a parallel bar pullup. This places the shoulder joint in a more neutral position which is not only safer but will place your joints in a stronger stance throughout the motion. Keeping your elbows forward, press the weight up in a straight line and then return slowly just before the dumbbells touch your shoulders.

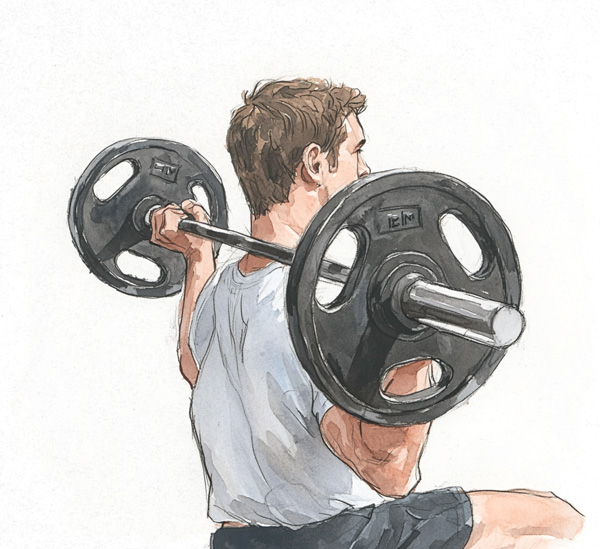

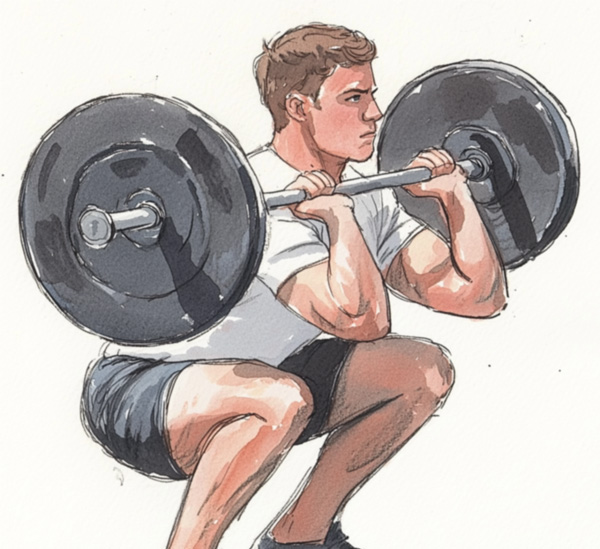

Front squat

The front squat is a highly effective and uniquely qualified exercise for a few important reasons. One, it places the spine in a more upright position (all the while demanding more activation from your core), and two, it can stress more quadriceps stimulation and place less load and stress on your lower back, glutes, and hamstrings. All in all, it’s a great exercise for targeting quads and lowering the undue stress on your back–for the experienced lifter.

There are several factors at play here that make this movement a bit of a challenge for optimal results. One, for most lifters it’s very difficult to hold the weight on the front rack of their shoulders while being under stress of exercise execution. Two, take that challenge and you can see how it would be very tough to effectively overload your lower body. With most of your attention focused on holding, balancing, and straining to keep the weight in the proper position, your efforts to push your quads to their max become a not so top priority.

If you’re the type who’s a rockstar with front squats then by all means go for it. But if you’re like me and many other lifters and just can’t keep the bar in position, then stick to perfecting the traditional back squat, take on the goblet squat, and maybe even adopt the Bulgarian split squat. You’ll have much more stability and success with overload and stimulate more muscle fibers for growth and strength. .

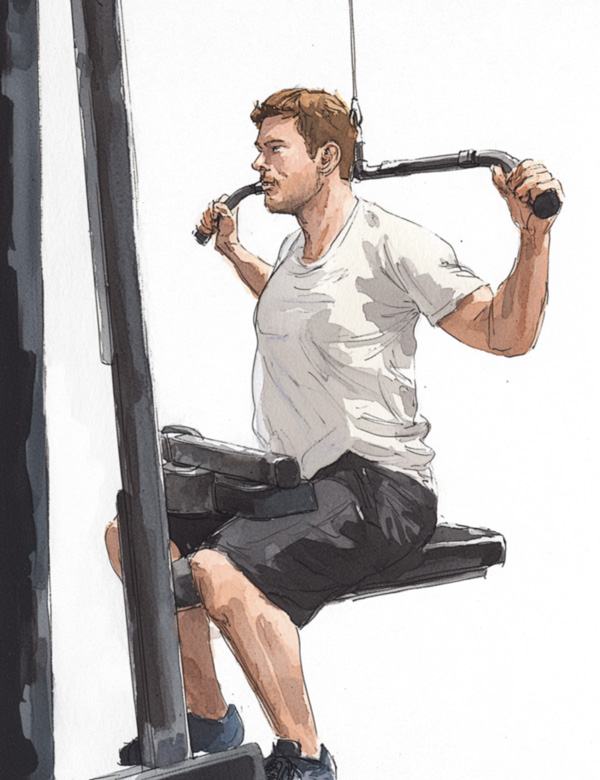

Behind the neck pull-down

Much like the behind-the-neck shoulder press, the behind-the-neck pull-down runs the same set of grievances and risks. From external rotation of the shoulder to the inability to optimally overload the targeted area, this exercise can cause serious potential risks with little benefit. The ratio just isn’t worth it.

Yes, it does target some pretty specific areas of the back, especially the upper back, but as far as giving you the most benefit for your time and effort, it just doesn’t stack up. To properly use this exercise means to lift a very light load in the strictest form possible–and that’s if you’re built for it–read: have very mobilized shoulders.

You’re better off choosing pull-ups, chin-ups, front pull-downs, barbell and dumbbell rows, and machine rows. With those exercises, you’re in a more advantageous position to overload your back and increase load as you get stronger without a high risk of injury.

Too much isolation work

A timeless practice I see daily is lifters (usually beginners) prioritizing isolation movements first in their routines. They’ll come in and start with chest flys, concentration curls, or a ton of cable work before attempting any of the bigger, compound moves.

What’s the difference? Simply put, compound movements utilize more than one joint while isolation moves only use one joint. So any pressing types of moves, squats, deadlifts, and rows are considered a compound, and moves such as curls, triceps extensions, calf raises, and flys are considered isolation.

Isolation work does have its place in a program, but an overreliance on it will not only hinder increases in size and strength, it will also occupy too much of your time away from the bigger, more optimal exercises. Compound moves use the most amount of muscle, multiple muscle groups at once, and burn the most amount of energy (calories).

Take an 80/20 approach to exercise selection. Eighty percent of your exercises should be from the big compound moves such as all forms of barbell and dumbbell bench presses, and squats while 20 percent can come from isolation moves like curls, flys, and most cable work. Programming this way will give you the best of both worlds: more muscle and strength and the sometimes fun act of finishing off with some isolation work.

Glute bridges/hip thrusts

Sometimes trends happen for good reason. A few years ago the term posterior chain got a lot of buzz. It comprises the often-forgotten posterior muscles such as the hamstrings, glutes, and lower back–muscle groups you can’t see in the mirror when facing it. Some trainers may even include lats, traps, and rear deltoids. Nonetheless, the glutes specifically received a huge spotlight and even garnered a “new” exercise to many: the hip thrust.

This attracted many to adopt it as the go-to exercise for not only a rounder, stronger booty but to also create more functionality for athletic goals.

Now, the hip thrust is a great exercise, but right along with too much focus on isolation work, the hip thrust became the backbone of many lifters who wanted a shapely butt. This overreliance did something else a bit detrimental. It thrust (pun intended) the true drivers of a stronger glute area into the backseat. Exercises such as free weight back squats, lunges, and Romanian deadlifts got less attention while everyone was glute bridging away!

The bottom line is, as a beginner, to include those tried and true squats, lunges, and deadlifts before delving into more isolated moves like the hip thrust. Sure, you can still include them in your routine, but don’t forget those other big compound moves that may seem basic but are incredibly effective.

Smith machine work

Finally, we get to the coveted Smith machine. As a universal gym tool, the Smith machine can be utilized for a variety of upper and lower body exercises. Everything from squats and deadlifts to bench presses and rows, it’s a great alternative to free weights for a change of pace or working around an injury.

But here’s the rub: since it glides on a fixed path, your natural arcs of movement can become compromised. This presents a couple of problems. One, it prevents you from learning your personal path of movement. Your limbs have natural arcs, unique bar paths, and a specific flow all exclusive to your body type. The Smith machine won’t take under consideration your arm and leg lengths, your trunk length, and any other definitive mobility issues. In turn, you’re prevented from learning balance, stability, and, subsequently, strength.

Two, since the bar is fixed on a rigid path, your joints don’t have a chance to “breathe.” Over time they can become locked into a harsh cadence all the while not allowing your joints to adjust, shift, and adapt the load. It’s best to stick with free weights such as barbells and dumbbells and use the Smith machine only seldomly.

In closing

There can be nothing more exciting sometimes than to start a new program to build muscle and strength–to reshape your physique and mold it into something you can be proud of inside and out. If you’re a beginner, try not to jump into the first thing you see on social media or Youtube filling your program with a ton of filler, trends, and fodder. Take a more practical, well-thought-out approach that will produce long-lasting results that will stick to your bones.

Source link

#Exercises #Successful #Bodybuilder #Beginners