It’s July 27, 1847. My third great grandparents and their four children step from the gangplank of a crowded three-masted ship onto a pier in lower Manhattan. Thomas Carolan is 40, Elizabeth Smyth, 30, children Bessy, 13, Catherine, 4, Michael, 3, and Annie, 1.

They’ve been 34 days at sea in the deadliest year of An Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger. Called ‘Black 47’ for the disease, death, and emigration caused by England’s response to the people living in her richest Kingdom in an unparalleled environmental catastrophe.

The Carolans are among 3,671 arriving this week in New York—faces of hope streaming off the square-riggers berthed on the East River along the storied “Street of Ships.”

Theirs is called the Patrick Henry—named for the patriot famous for “Give me liberty or give me death”—a packet ship with 16 sails, over half a football field long.

The Carolans are among her 315 passengers on the ship. Her steward Peter Ogden will organize the largest US fraternal organization for Blacks, and her captain Joe Delano will become first cousin, twice removed of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The actual President the year they arrive is James K. Polk, America’s second President said to be of Irish descent. It’s still three decades before a US President’s first to visit Ireland: Grant in 1879. And still to come are the voyages of the ancestors of Biden and Obama.

Standing in New York with water lapping at the sides of their home for the last 34 days, Tom and Lizzie can’t imagine that in a few years only two of their four children will be with them—Kate and Mike.

Nor can they imagine they’ll have six more healthy ones, raised on a farm outside Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, over the next 15 years: Julia Ann, Thomas Spencer, Martha, Anna Elizabeth, Lydia Tyson, and Mary Emma—thanks, in large part, to the generosity of an old childless Quaker couple, the Spencers, whose name will be passed down by my family for generations.

Nor that their eight children will produce thirty-one grandchildren and multiply exponentially, like every other immigrant family. In fact, similar feelings of dispossession and forced migration are with us today more than ever. At the end of 2020, one in every ninety-five people on earth—over 82 million—had fled because of conflict, persecution or natural disaster. More than 200 million will migrate over the next 30 years because of weather or environmental degradation. And there’s famine: in 2021 the U.N. estimated more than 500,000 were suffering from catastrophic conditions worldwide, with 45 million at emergency levels of hunger.

At the same time, this year, the population of Ireland finally rose back up to levels it had not seen since the Great Hunger.

From the logbook of the ship on which Carolans arrived, the passenger manifests, baptism registers, census records, newspaper accounts and family narratives, we reanimate the journey of a singular American family, to represent millions around the globe today.

The descendants of survivors who celebrate their escape, honor the memory of victims, and assimilate into larger, reinvigorated versions of themselves.

Children of Thomas Carolan (1806-1870) & Elizabeth Smyth Carolan (1817-1876), Various dates. Four of eight children who survived into adulthood. L-r clockwise, Michael Carolan, 1844-1906, On board the Patrick Henry at age 3; Julia Ann Haughey, 1849-1905; Martha Tansey Guppy, 1852-1929; Thomas Spencer Carolan,1852-1915. Courtesy Ann Carolan Moerk, Elizabeth Haarlander, Nathan Kelley & Michael Thompson.

The Carolans forced to leave Ireland

On the Patrick Henry, Tom brings his 13-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. It’s 1834, and Father Nicholas McEvoy baptizes Bessy outside of Kells, at a crossroads called Light Town—so named for the candlelit, foot-square windows of its cabins.

He handwrites “illegitimate” on her birth register; her mother’s name is Bridy, but Tom raises her.

Pastel, Carolan Homestead, Melissa Carolan Gouffray, sister of author, 2022. Photo by Conor O’Brádaigh. The residence of Emigrant Thomas Carolan’s grandfather, father and older brother, built about 1800. Light Town, Springville-Dandlestown Townland, Kells Parish, County Meath. Today held by the O’Brádaigh (Brady) Family, related by marriage.

Tom then marries Lizzie (Elizabeth Smyth), who is soon pregnant. First comes Kate, and then Michael in 1844.

The following year, their priest counts more than 50 wagonloads of food headed for the port from which the Carolans will depart. “With starvation at our doors, grimly staring us,” McEvoy writes presciently in The Nation, Oct. 25, 1845, “Vessels laden with our sole hopes of existence, our provisions, are hourly wafted from our every port.”

Annie is born in 1846. Soon the government is providing 2,000-plus inedible “portions” of porridge etc., every week, and a mob revolts, claiming it “an offense to the dignity of the people.”

“While I write the streets of Kells are crowded with men,” writes a correspondent for the London Morning Post on May 24, 1847. “All the bread and provision shops are closed up; the town is full of consternation….” Four years later, there’ll be 1,347 townspeople in a workhouse built for 600 and mass burials at the Kells Union Paupers’ Graveyard.

By the time the Carolans leave, Ireland is a virtual warzone, with the constabulary, militia, and more than 30,000 troops, including the 68th Light Infantry at Kells.

They evict people, quell crime, and protect the rich exports from Irish ports, including the following sample, published by the London Times, of one week ending July 8 & arriving at Liverpool: 1,228,950 pounds butter, 345 tons wheat, 2,381 sacks wheat, 2,004 barrels flour, 148 tons oats; 43 tons oatmeal, 251 oxen, 152 calves, beef, pork, whiskey & 782 barrels of Indian corn meal….

Police are making arrests; assizes are full; convicted men and orphans will soon be sent to Australia.

Outside Kells, calves, sheep, and rabbits are slaughtered on the spot upon the estates, including John Nicholson’s, the Carolans’ landlord. He wants his 8,000 acres put to pasture, to fatten cattle, and is said to pay for the Carolans’ passage, according to the National Folklore Collection.

“Give me liberty…”

Tom arranges for the horse-driven Bianconi Coach that runs them 25 miles to the Drogheda Steam-Packet Company, where they pay five shillings a head to catch the St. Patrick to cross the Irish Sea for Liverpool.

On June 23, 1847, the daytime high is 63, showers at noon, winds W-NW, and a ship—recently arrived from America with food in her hold—is ready to return.

And the Carolan family is off, heading for the New World, in the Patrick Henry, of Grinnell, Minturn & Co.’s Swallowtail Line, “one of the best and most dependable packets of the era.”

Their passage costs around $650 each, in today’s dollar, for a combined 8 x 6 x 3-foot-high steerage berth, if lucky. First-class pay more than $4,000.

After 10 days at sea, everyone is through their seasickness and Bessy is helping her stepmother with the toddlers.

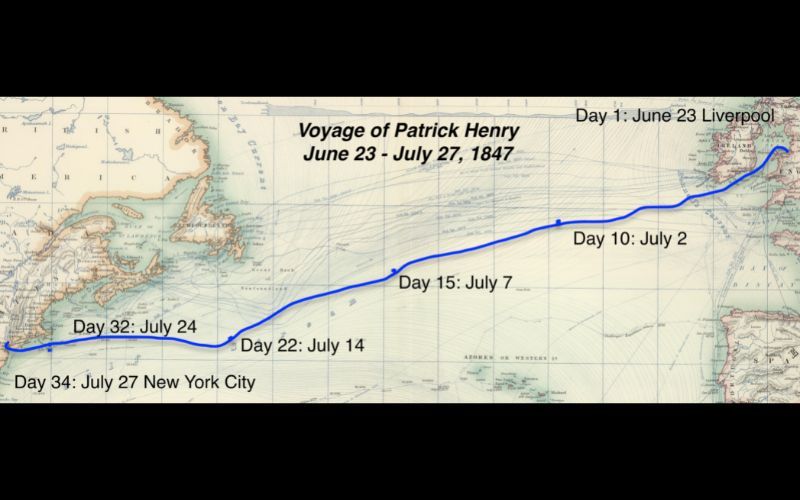

Voyage of the Patrick Henry, Author, 2022. From ‘Basin of the North Atlantic Ocean,’ 1879, Keith Johnston. (Public domain)

On July 2, they are 669 miles beyond Tuskar Rock, averaging 3.5 knots. They climb up to the bulwarks and see the smaller packet Samuel Hicks off the bows.

The next week, day 18, they are 1,500 miles from Liverpool and averaging a whole 6 knots. The British bark Emigrant crosses their path.

As for life on board, the women sew and knit,

…tradesmen made money repairing shoes and clothes; boys and girls copied the characteristic rolling gate of the sailors or danced to the tune of the diminutive Irish fiddler, who played as indefatigable as a dummy cranked up after every song. During these few hours when gaiety surmounted the underlying sadness, anxiety, and fear the crowded foredeck was like a bit of Ireland revisited.

Nearby the sailors and apprentices listened to the infectious music and shouts of joy, swabbed decks, mended sails, tarred ropes, spun yarns, and chopped broken spars into firewood.

On July 14, day 22, on deck, Lizzie is holding Annie and sees a ship in the distance, sailing in their direction, with “a cross in her foretopsail.”

Ten days later, day 32, Land-ho! Nantucket and little Michael’s third birthday with song and extra biscuit.

Three days later, the family is on deck, gazing as Manhattan’s southernmost point sweeps by, where “green lawns surrounded The Battery and promenading ladies and gentlemen could be seen through the foliage.”

Soon, South Street “and the many ships tied to her flank, their tangled thicket of masts and rigging almost concealing the dingy warehouses behind them.”

View of South Street, from Maiden Lane, New York City by William James Bennett circa 1827. (Public Domain / Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Suddenly, the “chorus of welcome” and “questions and answers between the sailors aboard the tied-up ships and those aboard…” the Patrick Henry. Captain Delano takes roll; there have been no deaths on the voyage through a New York newspaper claims 288 in steerage while the manifest shows 297.

In Canada, it’s far worse this summer. By year’s end, there are 89,738 arrivals, 5,293 die during passage and 10,029 perish soon after.

Back in the Carolan’s former townland in Ireland, the population plummets 54% in a decade. Three decades later, its 50 houses are reduced to 11.

In 2011, there are only 4, one of which is “vacant.” That’s the two-story stone home of my ancestors, held today by family related by marriage. (See: Éireann’s exiles – reconciling generations of secrets and separations.)

In celebrating the 175th anniversary, I have contacted descendants of each of Tom and Lizzie’s eight children, many still in Philadelphia.

That’s the birthplace of my great-grandfather Matthew, grandfather Walter and father William.

And for a little synchronicity—my father’s birthdate is July 24. That’s precisely 93 years after, to the day, of the birth of Michael, his great-grandfather, the three-year-old who sailed on the Patrick Henry.

Happy birthday, Dad.

*Michael Carolan is a Professor of Practice in the Department of English at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. He lives in Belchertown.

Sources:

- Newspapers: New York Daily Tribune. New York Herald. Liverpool Mercury. Evening Post (London), London Times, Meath Herald & Cavan Advertiser (Kells), Anglo-Celt (Cavan)

- Connell, Peter. The Land and People of County Meath (2004).

- Gallagher, T.M. Paddy’s Lament: Ireland 1846-1847: Prelude to Hatred (1985)

- Fairburn, W. A. Merchant Sail (1945).

- Fogarty, C. Ireland 1845-1850: The Perfect Holocaust and Who Kept It ‘Perfect’ (2014).

- Measuring Worth, www.measuringworth.com.

- National Archives of Ireland (https://www.nationalarchives.ie/); Census of Ireland, 1841-1871; 2011.

- National Folklore Collection, The Schools’ Collection, Co Meath, Drumbaragh, Volume 0703 (1939).

- Slater, compiler. (Royal) National Commercial Directory of Ireland (1846)

- Steamships of Drogheda. http://www.droghedaport.ie/cms/publish/printer_163.shtml.

- Vane, W.L. The Durham Light Infantry (1914).

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.