The story so far:

The Ukraine conflict has witnessed dramatic developments in recent weeks. U.S. President Donald Trump has brought in a 180-degree shift in U.S’s policy towards the war. Disagreements between Kyiv and Washington on how to end the war have led to an unprecedented public spat between Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Mr. Trump in the Oval Office, following which the U.S. paused all military aid for the war-torn European nation. Within a day, Mr. Zelenskyy ‘regretted’ the spat, announced Kyiv’s readiness to declare a partial truce and work with Mr. Trump to achieve lasting peace. Europe seems caught off guard as the geopolitical glacial plates are shifting fast. Russia is watching and waiting, while the war grinds on.

Also Read: What Trump 2.0 means for Russia and Ukraine: In graphics

How did the war begin?

When Russian President Vladimir Putin launched the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, he probably thought the war would be over within days. So did Ukraine’s western partners, including the U.S., who vacated their embassies in Kyiv right before the war began. But when Ukraine, armed with U.S.-supplied weapons, denied a quick victory to the Russians, the West stepped in. The U.S., under the Biden administration, adopted a two-pronged approach towards the war — impose biting sanctions on Russia to weaken its war machinery and economy, and arm Ukraine to the teeth to fight the Russians on the battlefield. “We want to see Russia weakened,” Mr. Biden’s Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin said in April 2022. This approach was relatively successful in the war’s initial phase. By September 2022, Russian troops were forced to withdraw from the settlements they had captured in the Kharkiv Oblast in the northeast. In November, Russia pulled back forces from Kherson city and parts of Mykolaiv on the right bank of the Dnipro River in the south.

But in between Russia’s retreats from Kharkiv and Kherson, President Vladimir Putin had doubled down on the war: he annexed four Ukrainian oblasts — Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson — and announced a partial mobilisation. The message from the Kremlin was that it was ready to fight a long war. On the economy front, Mr. Putin pivoted towards Asia where the huge markets of China, India and others helped Moscow offset the impact of the sanctions.

Where does the war stand today?

In 2023, Russia gradually turned the tide of the war, inch by bloody inch. It took Soledar in January and Bakhmut in May, after a months-long campaign. In 2024, Russia expedited its battlefield advances by capturing Avdiivka in February, Krasnohorivka in September and Vuhledar in October. At no point since 2023, had Ukraine seemed capable of defeating the Russians and recapturing the lost territories. In June 2023, Ukraine launched a much-awaited counteroffensive, with advanced western weapons, in the south, but it fizzled out in the face of Russia’s dogged defence.

Also Read: A high-stakes power play — Trump, Putin and the Ukraine war

In August 2024, Ukraine captured some 1,000 sq. km of Russian territory in the Kursk region in a surprise attack aimed at mounting pressure on Russia’s advancing troops in the east. But Russia refused to walk into the trap and pressed ahead with its offensive in the east, the soft belly of Ukraine’s resistance. In 2024, Russian forces captured an estimated 4,168 sq. km in both Ukraine and Russia’s Kursk. In January 2025, Russian troops seized Velyka Novosilka and parts of Toretsk. They have also been trying to encircle Pokrovsk. Ukraine in recent months stepped up drone and missile attacks deep inside Russian territory as well as in the Black Sea, hurting Russia’s security. But on the battlefield, it has been on the backfoot for over two years.

Why has Trump changed America’s Ukraine policy?

Mr. Trump had promised during his election campaign that he would bring the war to a quick end. After taking office in January, he moved fast. First, Pete Hegseth, the U.S. Defence Secretary, told the Ukraine Defence Contact Group, an alliance of 57 countries and the EU put in place by the Biden administration to help Kyiv, that Ukraine would not become a NATO member. He also ruled out American security guarantees for Ukraine and said any European guarantee would not be covered under NATO’s collective security clause. Immediately after Mr. Hegseth’s comments, Mr. Trump held a telephone call with Mr. Putin. Within days, Russia and the U.S. had two rounds of direct talks. Mr. Trump seems determined to reset America’s ties with Russia.

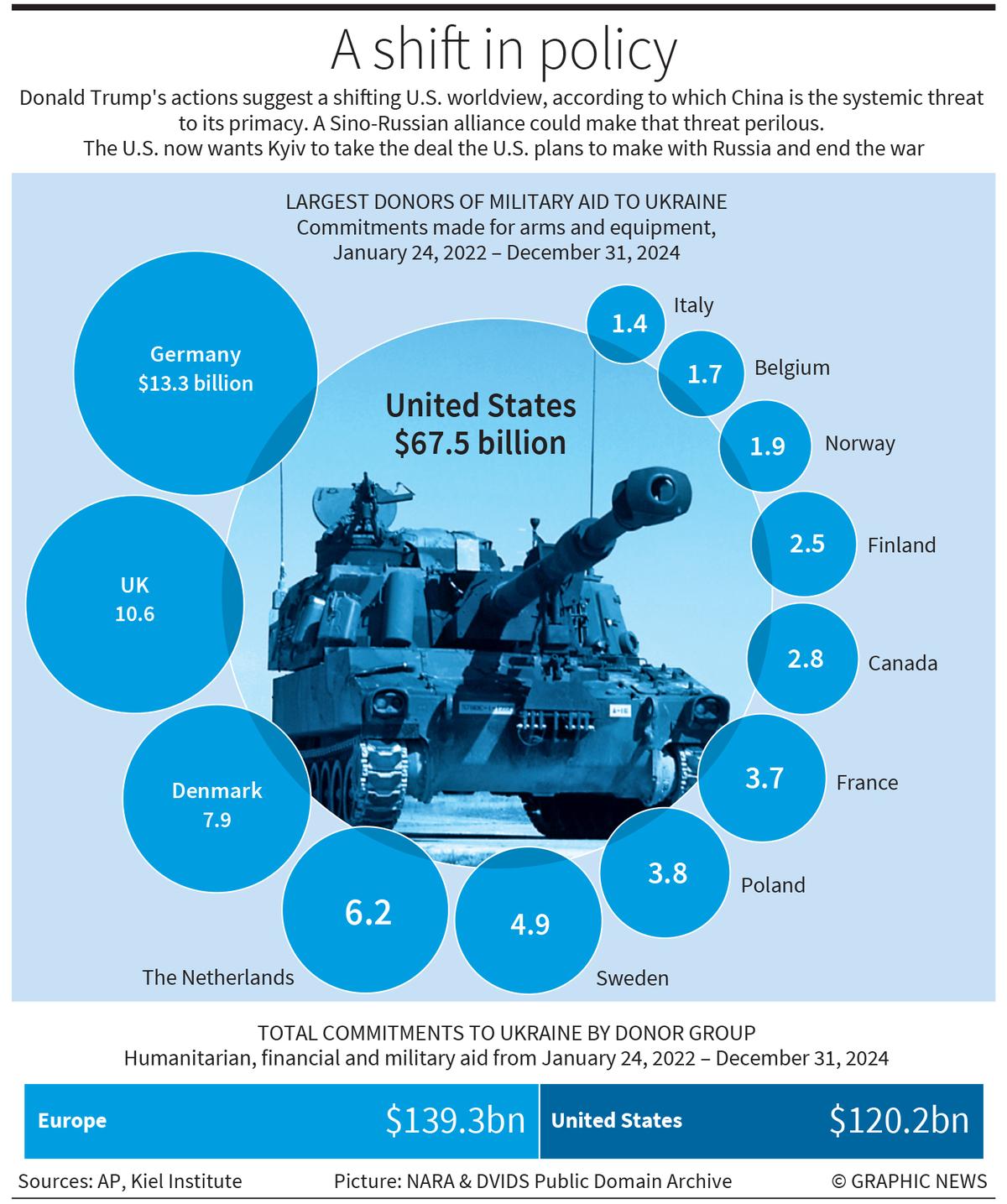

One explanation for this approach is that the U.S. doesn’t see Russia as a threat any more. The U.S., in that sense, is breaking with the post-Second World War trans-Atlantic consensus, and is going back to the pre-First World War offshore balancing (the U.S. is protected by the world’s two greatest oceans and shares borders with two meek powers in the south and north). In this Realist worldview, China is the systemic threat to the U.S’s primacy and a Sino-Russian alliance could make that threat perilous. It would entail a reorientation of America’s policy towards Russia — in a reverse order of what Henry Kissinger did in the 1970s when he and President Richard Nixon exploited the Sino-Soviet split and reached out to Beijing. In this grand reset plan, Ukraine is just a hindrance. Mr. Trump believes Ukraine can’t win the war even with American support, and wants Kyiv to take the deal the U.S. plans to make with Russia and end the war.

How does Europe look at the developments?

Europe seems to be struggling to come to terms with what’s happening. When Ukraine was promised NATO membership by U.S. President George W. Bush in 2008, Germany and France were hesitant. After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 and supported a rebellion in Ukraine’s east, Germany and France played a role in negotiating the Minsk process to bring peace to Ukraine. But the U.S. was not very keen on the Minsk accords, and continued to back Ukraine militarily. No side — Kyiv, the separatists in the east, and Russia — implemented the accords. The crisis escalated into a full-blown war on Europe’s watch. After the war began, Europe had to pay a huge economic cost. The Nord Stream pipeline, linking Russia across the Baltic Sea to Germany, was blown away (most likely by the Ukrainians, according to American media). The stoppage of the flow of cheap Russian gas triggered a cost-of-living crisis and de-industrialisation, which deepened public antipathy towards Europe’s political establishment in several countries. For example, Germany is in recession for the third consecutive year, and the German far-right is ascendant.

Also Read: Endless war: On the Russia-Ukraine war

And now, the U.S., which was in the lead of the pro-Ukraine alliance, is breaking with the policy and directly talking to Russia, excluding both Ukraine and Europe. European countries have called two summit-level meetings since Mr. Trump came to office, and promised to do more to help Ukraine. But the question is whether Europe, which itself is divided, has the capacity to provide security guarantees to Ukraine without America’s backing. At present, Europe doesn’t have many options but to go with the American plan. Europe also has bigger problems than Ukraine. It is worried about the future of NATO as the Trump administration is reorienting America’s post-War foreign and security policy.

Where does it leave Ukraine?

Ukraine has lost more than 20% of its territories to Russia and tens of thousands of soldiers were killed in the war. Millions of Ukrainians have fled the country. Its economy is in shambles, and the energy sector is facing a major crisis because of Russia’s repeated bombing of its infrastructure. The country is dependent on external supplies to meet at least half of its weapons requirements — including artillery and ammunition. Ukraine is also facing a manpower crunch on the battlefield (Mr. Trump says Ukraine is “running low on soldiers”, while Vice President J.D. Vance says Russia has a “huge numerical advantage”).

The country is therefore in dire straits. The U.S. says it’s not practical to expect Ukraine to retake its lost territories — the Ukrainians and Europeans would grudgingly agree. The U.S. promised NATO membership to Ukraine in 2008. In 2025, the U.S. says Ukraine can forget about NATO membership. Ukraine wants at least security guarantees, but America is reluctant to provide any such guarantee. So, if Ukraine continues the war, it could lose more territories. If it stops the war, it will have to do so on the terms set by Russia and America. In the outset, no good options left for Mr. Zelenskyy and his Generals. Great powers fight proxy wars when their interests clash. Great powers reset ties when their interests align. The pawns and proxies suffer. Ukraine’s story is not different.

Published – March 06, 2025 08:30 am IST

www.thehindu.com (Article Sourced Website)

#history #RussiaUkraine #war #Explained