At Home in Sittilingi is an exhibition of embroidered textile art created by 10 women artisans from the Lambadi community. The works are stitched on organic cotton and draw from memory and immediate surroundings — trees that surround them, stories heard from elders, birds marking seasonal change, millets grown in their fields, and the intricacies of domestic life.

Held at Sabha, a thoughtfully restored 160-year-old home in Bengaluru with quiet floors and sunlit corridors, the open, home-like setting lends the show a sense of intimacy. Visitors leave their shoes at the threshold, entering barefoot — an unspoken gesture of reverence and groundedness. This simple act changes the way we engage. We step softly. We pause longer. We meet the works not as distant observers, but as listeners in a room full of stories. The anecdotal texts accompanying each embroidery, written by the women themselves, add texture and voice, making the gallery feel less like a display and more like a gathering.

Sabha’s open, home-like setting lends the show a sense of intimacy

| Photo Credit:

R Kishore Kumaar

At Home in Sittilingi at Sabha

| Photo Credit:

R Kishore Kumaar

An ‘at home’ residency

The works were developed through a four-month artist residency hosted by the Porgai Artisans Association during an “at-home” residency, an artist support model where the women continued to live and work within their own context (at a studio at the Porgai centre) rather than being displaced into unfamiliar institutional settings. Curated by designer Anshu Arora, the residency invited the women to reflect, remember, and reimagine from within their own ground.

Geetha, one of the 10 artisans, holds up her artwork embroidered with green bee-eaters

| Photo Credit:

Melanie Hinds

Lalitha Regi, co-founder of Porgai, meaning pride and dignity in the Lambadi dialect, and a senior doctor at the Tribal Health Initiative, offers insight into the complexity of participation: “The women had to make many choices in their domestic lives before committing to the residency. It required them to travel 12 kilometres — an unremarkable distance for us, but a world of variables for them. Catching the one bus, ensuring people at home are fed, children taken care of, chores and farm labour attended to… each of their lives holds its own intricate challenges. Once they were made to feel safe, financially and emotionally, and given ownership over their work and creativity, we saw magic.”

That atmosphere of trust and co-creation shaped the work itself. Over the months, hesitation gave way to confidence, and the familiar grammar of Lambadi embroidery transformed into something layered, narrative, and imaginative.

Many of the embroideries carry a playfulness that feels both deliberate and deeply personal: a crooked-beaked bird, a smiling cow, a parrot with twinkling eyes, a bee-eater offering a subtle wink. These are not naive embellishments, but visual signatures of a relationship with the natural world that is familial, reciprocal, and full of mirth. The flora and fauna in these textiles are not passive scenery. They are kin. There is humour, memory, and mischief sewn into the leaves and wings — suggesting a way of being with nature that is less about dominance and more about camaraderie.

Two of the Lambadi women with their artwork

| Photo Credit:

Melanie Hinds

Rejecting curation as an act of control

The Association has been active in Sittilingi for over 18 years. It began with the revival of Lambadi embroidery and has grown into a cooperative model that centres the artisan not as labourer, but as knowledge holder, designer, and cultural custodian. Today, the collective has 60 women. They are paid fairly, retain control of their process, and make decisions as a group.

The curation of this exhibition reflects that ethos. “Too often, curation becomes an act of control — an exercise in authoriality,” says Arora. “With Porgai, I wanted to hold space without shaping it. The artists already know what they want to say.”

Firewood collection

| Photo Credit:

Vandita Bajpai

Each artist began with a six-inch square. The modest frame served as scaffold and possibility. From there, they embroidered both independently and together, shaping works that were at once singular and collective, a total of 26 pieces — the smallest being 21” x 11.5” and the largest being 50” x 36.5”. In some cases, they stitched their imaginations side by side: 10 interpretations of the sky, each in a different hue, texture, and mood, were sewn together into a larger tapestry of atmosphere.

10 interpretations of the sky

| Photo Credit:

Melanie Hinds

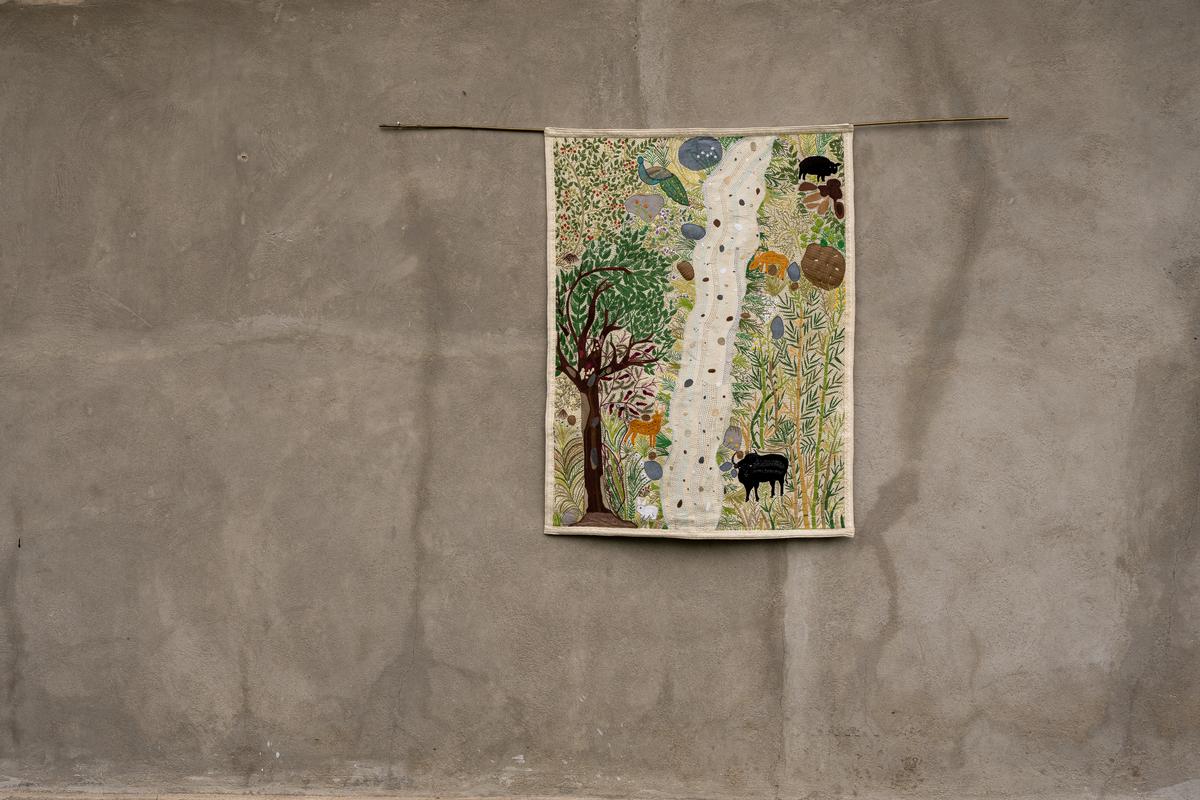

In another, they explored the ground beneath their feet, rendering stones, shadows, leaves, and soil with a sensitivity to texture and light. Other works emerged through collaborative storyboarding: large pieces of fabric were mapped and divided among them to depict scenes of daily life — a wedding, an agricultural routine, the choreography of water collection. They used more than 21 traditional Lambadi stitches (such as the maki and bhurai) and some newly invented ones by the artisans.

Each work is accompanied by a note from its maker. Neela speaks of ancestors. Lavanya dreams of bees. Parimala embroiders the Porgai centre so her grandchildren might remember it. Selvi’s stream flows with layered fabric mimicking rock undulations.

Neela, who speaks of ancestors

| Photo Credit:

Himanshu Dimri

Arora also situates this ethos within a broader design discourse. “The definition of luxury is changing. It now is about objects with a story and human connection — handcrafted, speaking of the person behind the item, made slowly and deliberately, with care, ethics, and non-exploitative systems in place. The rich textiles and crafts of our subcontinent are coming alive beautifully in this light.”

Beyond revival

In India, the art world continues to reflect caste and class divides. “Art” is gallery-validated, urban, and elite. “Craft” is rural, feminine, lower-caste — and systemically undervalued. Porgai rejects this binary not through argument but through assertion. These are embroidered works with conceptual clarity, formal integrity, and cultural density. They are art. They are testimony. They are systems of knowing.

Artworks with conceptual clarity and cultural density

| Photo Credit:

Himanshu Dimri

As Arora notes, “A lot of textile designers and professionals in allied fields are doing revival work. I hope we all keep up with nourishing these communities in ways that make them self-sustaining. As designers and facilitators, the success of our work is when it is temporary — when we can step out eventually, and what we started has a life of its own, runs itself, and blooms and prospers by the people at its core.”

Porgai holds precisely that promise. It is a body of work where process and product align, where care is not an afterthought but the method. It reveals that aesthetics need not be detached from ethics. That making can be mutual, and beautiful things can be made without violence.

At Home in Sittilingi is on view at Sabha till tomorrow.

The essayist and educator writes on design and culture.

Published – April 26, 2025 06:12 pm IST

www.thehindu.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Square #roots #Lambadi #artisans #stitch #ordinary #extraordinary